Sound

Design

At Murdoch…

Sound incorporates the way sound is used both in media and in everyday life. In music recording, film sound, game sound and industrial sound design professionals create the recognisable sounds of the modern world and create new sounds. This major focuses on the practice of contemporary sound design and production, combining a mix of theory and practice in areas such as music, sound design for film and television, live performance such as music and theatre, and interactive media like video games, simulations, AR and VR.

Our “Students”

Their “Stories“

Want to see what it’s like to study here?

Watch the video to hear from our students

and discover their stories.

Javiera

Ortega

Our Student’s Work

Audio mindfulness Project

The Audio Mindfulness Project was established as part of the Boola Katitjin creative works initiative.

The project was conceived as one where students developed audio material to assist Murdoch student’s in improving their mental health and well-being by accessing meditative narratives.

The scripts based on the themes; Body, Emotion, Environment, Mind and Persona were written by Psychology students developed the scripts, Drama students then voiced the scripts with Audio students recording the scripts and producing musical and atmospheric backing to the voice pieces.

Script writers …………..

Voice Actors: Jaimee Gardner and Jackson Billington

Voice Recording: Kim Funk and Max Perin

Music Composition: Olman Walley and Max Perin Production – Max Perin

Listen to the audio by clicking the ‘button’ below.

Scroll down the page to find the Audio Mindfulness Project section.

Bryan Austine Alegre

Anno Domini | The Kingmaker | A high-concept historical fiction radio drama

Set in London in 1878, during the transformative Second Industrial Revolution, the series is a historical thriller with each episode designed for a minimum runtime of 30 minutes.

The narrative delves into the high-stakes world of political manipulation and personal ambition. The protagonist, Thaddeus William Glass, is a self-made American industrialist whose influence clashes with London’s entrenched aristocracy. Frustrated by their resistance, Thaddeus forms a secret alliance with Harrington Sinclair, a British politician whose future is threatened by scandal. Their partnership—built on political debt—becomes the foundation for Thaddeus’s far-reaching ambitions. The plot thickens as Genevieve Thorne, a gifted and relentless investigative journalist, unearths their schemes, threatening to expose the truth. The story explores timeless themes: power, legacy, and the moral compromises made in pursuit of greatness.

Alicia Pepper

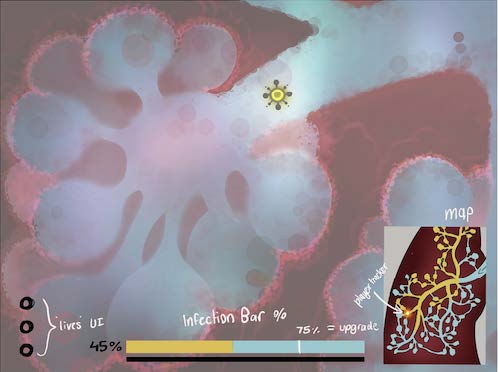

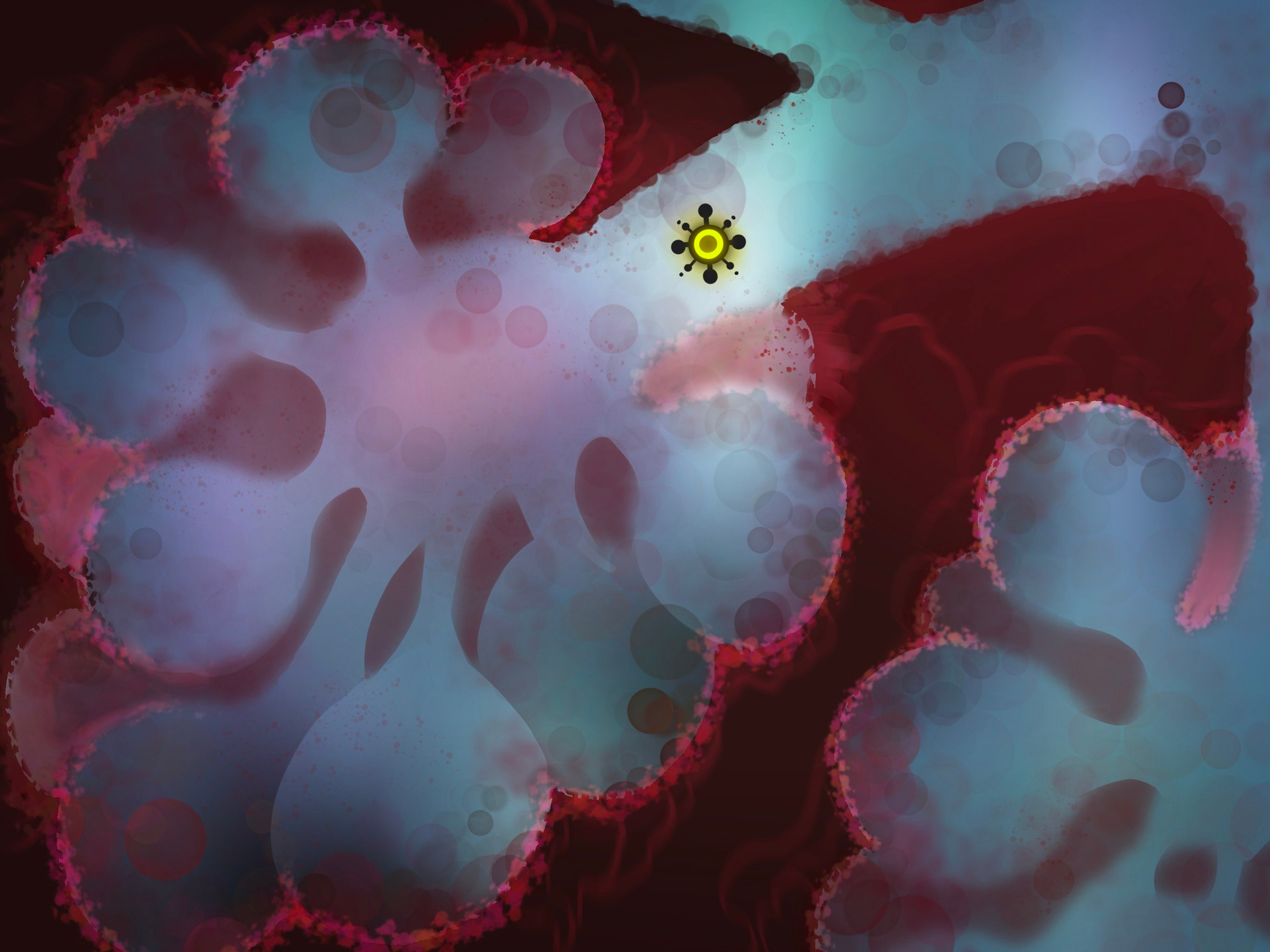

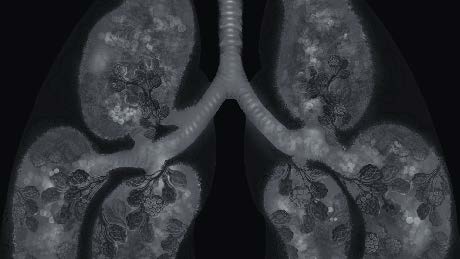

Sound Design | Pathogen’s Playground

Working with SAME Studios sound design for four different levels of the game was developed along with a Boss Theme and the Menu/Title Theme. The project involved the composition of diegetic and non-diegetic music and sounds for the markedly different levels in the game

Mitchell Whitehurst

Sound System design

The project took on the task of designing new sound systems for three Perth venues; Perth Convention and Exhibition Centre, Riverside Theatre, The Rechabite venue and the RAC Arena. The three venues cover a wide range of venues allowing the demonstration of design skills developed in Advanced Sound Production. Drawings and models of the spaces were developed as a design exercise.

Zoe Fenner

Podcast series | The Global Scholar

Studying abroad, can it really be helpful both personally and professionally? That is the question? The Global Scholar is a short podcast series that looks into how benefits gained from studying abroad can affect a person’s attitude towards the workforce. The idea behind this series is to educate young adults about the benefits that can be gained from studying abroad and how this experience can potentially influence their careers. There are four episodes in total, each ranging from ten to fifteen minutes, featuring a guest who shares a story about their experiences and how those experiences have shaped their personal and professional life.

Tim Scott

The Dark Side of the Bush Court |

Pink Floyd’s Quadraphonic album

At the time of its release (1973) The Dark Side of the Moon was available in a quadraphonic (4-channel) version. That aligned with the band performing live in a 4 channel format from 1967. The quadraphonic record format didn’t make it beyond the 70’s but with the advent of DVD-Audio and SACD versions of the 4 channel album were released in 2003.

A 4-channel sound system will be constructed on Bush Court and the quadraphonic album will be played in its entirety.

Tim Scott

Audio restoration and oral history

The City of Perth Surf Life Saving Club has over one hundred years of history, captured in sixteen audio stories, paired with an appropriate image that either shows the event spoken about, or is representative of what is spoken about. Thirteen club members were interviewed to create this series, along with two past interviews conducted with members which were restored and used in the series. The stories capture a range of moments throughout the club history, from historic competition performances to lifesaving conducted both at City and Denmark, as well as covering the social side of the club.

Story 1: Introduction

Photo taken from the 100 Year celebrations at the club in the 2024/25 season. The series that follows consists of moments selected from the clubs 100 year history that were researched and turned into short audio stories to document the history of the City of Perth Surf Life Saving Club. (City of Perth Collection)

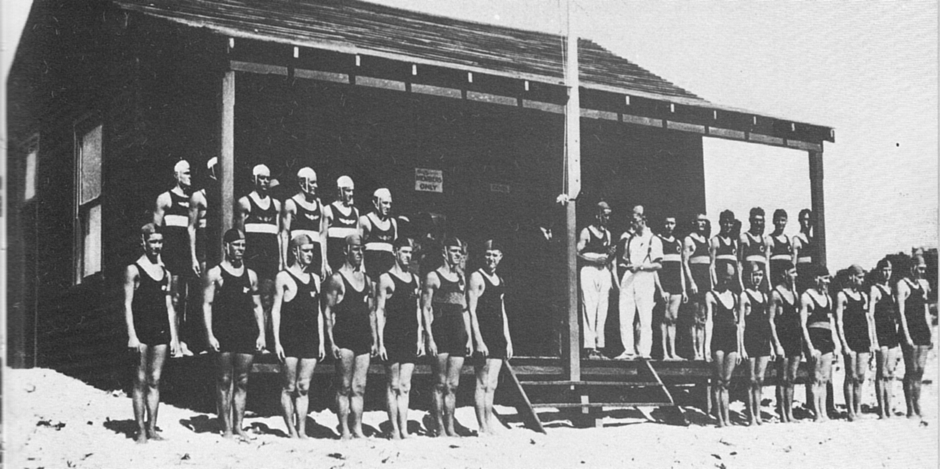

Story 2: Origins of the Club

Picture of club members in 1926, in front of the first clubrooms at the beach. (City of Perth Collection

Story 3: Wartime at City

Pictured are club members on an Easter trip in the 1940s. Jackie Mayberry pictured in the bottom row, third from the right. (City of Perth Collection)

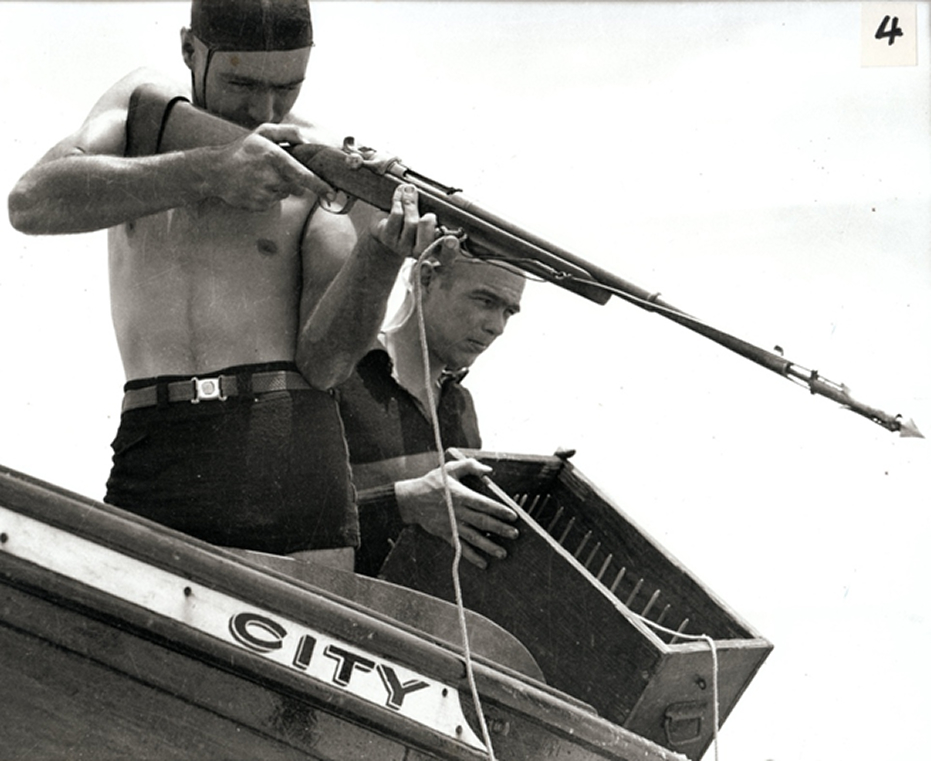

Story 4: 1946 Shark Attack

A staged photo of two club members firing the harpoon gun, sometime in 1940. (City of Perth Collection)

Story 5: Foundation of Denmark SLSC

Picture of the Denmark SLSC during one of City’s trips down there in 1962. Note the City of Perth boat jumper hanging up on the right of the image. (City of Perth Collection)

Story 6: 1971 Aussies

The City of Perth 1971 March Past team marching at the Australian Titles held at City for the first and only time in 1971. (City of Perth Collection)

Story 7: First Australian Title

The 1971 Junior Boat Crew, who won City’s first ever gold medal at the Aussies. Pictured from left to right Kevin McRae, John Leivers, Jim Pouleris, Dennis Trew and Robbie Somerford. (City of Perth Collection)

Story 8: Decade of Dominance

Team photo following the 10th consecutive State Championship (points) in 1987/88 season. “10 in a row” (City of Perth Collection)

Story 9: Women in the Club

‘Dennis Trew’s Female Crew’ The first ever female boat crew 1985. Pictured from left to right Jodie Morris, Bronwen Scott, Belinda Bennet, Laura Wenman and Dennis Trew. (City of Perth Collection)

Story 10: First 6 Person R+R Championship, 1990

Pictured (left to right): Ian Scott, Kate Bennet, Gordon Jones, Dave Armstrong, Jeff Scott, Peta Bennet, Mark Holland, Bronwen Scott. The clubs first ever 6 person R+R Championship. (City of Perth Collection)

Story 11: Harry Pinner’s Drowning, 1992

Photo of the groyne and tower on a rough day at City. The following story contains content that some viewers may find distressing. Viewer Discretion is advised. (City of Perth Collection)

Story 12: First Female President

Sue Scott during her reign as president of the club from 1992-96. Sue was the first female president of any SLSC in WA, and second nationally. (Scott family collection)

Story 13: 2005 Aussies

The Lifesaver Relay ream carrying under-17 James Cohen following his race-winning swim. The 2005 Aussies are the best in club history, totalling 10 gold medals, 7 silver and 3 bronze. The club finished 4th overall on the points score. (SLSA Collection – Harvey Allison)

Story 14: Alicia Marriot

In 2008 Alicia Marriot had an outstanding season, winning the Coolangatta Gold, placing second overall in the Kellogg’s Ironwoman Series, and capped it off with Aussies gold in the Ironwoman race at home at Scarborough. Alicia was the first Western Australian to win the Ironwoman at the Aussies. (SLSA Collection – Harvey Allison)

Story 15: The Concrete Bunker

The club posing in front of the clubrooms built in 1971, known as the ‘Concrete Bunker’ during its final days at City in 2014. (City of Perth Collection)

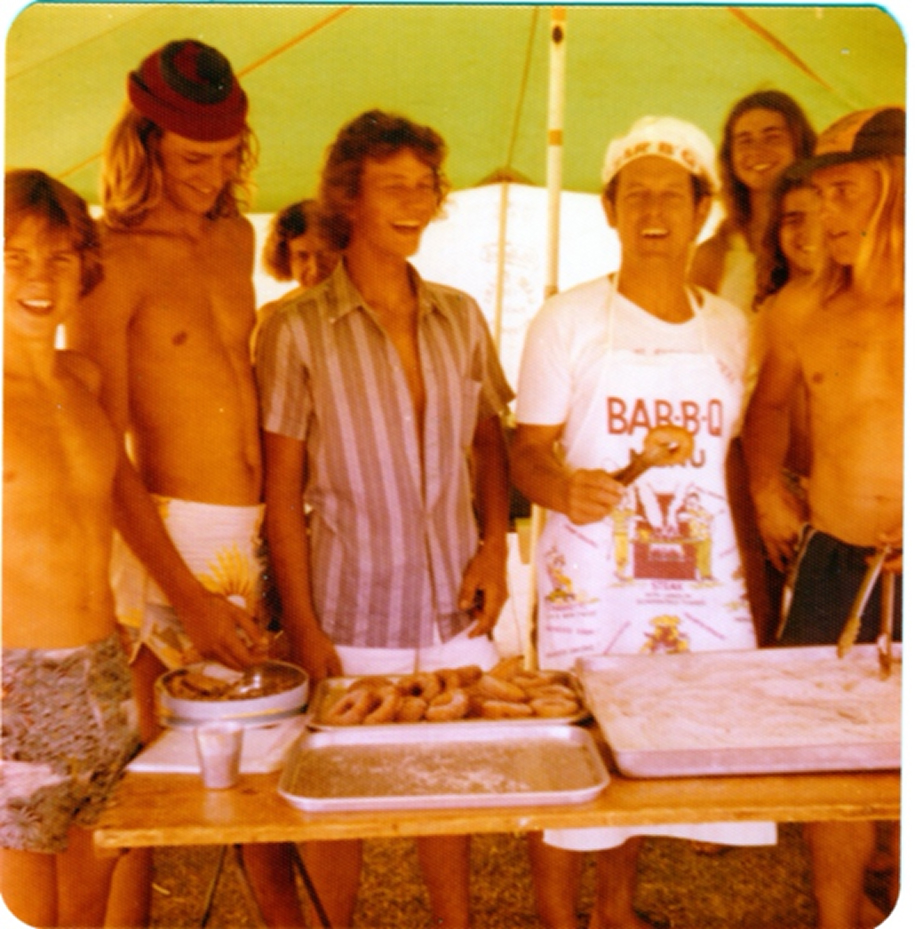

Story 16: Club Fundraisers

Club Legend Eugene ‘Mick’ Mickle running his donut stand at the City Beach Fair on Jubilee Park in the 1970’s. His son, Greg ‘Micko’ Mickle is furthest on the left. (City of Perth Collection)